On Friday 28 February

1975 the 08:38 service from Drayton Park on the London Underground Northern

line (Highbury Branch) left one minute late. It was formed of two three-car

units of 1938 LTE rolling stock. On arrival at Moorgate station the train

failed to slow, passing through the station platform area at 30–40 mph before

entering the 66 feet (20 m) long overrun tunnel with a red stop-lamp, a sand

drag and a hydraulic buffer stop. The sand drag only slowed the train slightly

before the train collided heavily with the buffers and impacted with the

terminal wall.

The smaller diameter of the tube train involved allowed the first car to ride up over the hydraulic buffers with the second coach driving under the first leading to significant damage at this end. The leading driving car buckled at three points into a V shape and was crushed to less than half its length between the wall and the weight of the train piling up behind it. The third car was damaged at both ends, more significantly at the leading end as it rode over the second car. Approximately 300 passengers were on the train; 42 passengers and the driver died and 74 passengers were treated in hospital for their injuries.

It was declared a Major Accident by both the Brigade and the London Ambulance Service. It was the LFB’s most difficult special service incident in over a decade. It was London’s worst-ever Tube disaster. The crash left the station in total darkness and threw up a huge amount of soot and dust.

Only one journalist was allowed down into the tunnel in the early stages- Gerard Kemp of the Daily Telegraph. He reported; "It was a horrible mess of limbs and mangled iron," he said. "One of the great problems [for the rescue teams] was the intense heat down there. It must have been 120 degrees. It was like opening the door of an oven." Twelve hours after the tragedy, a young policewoman was brought out of the front carriage after her foot was amputated. The last known survivor, a 26-year-old man, was brought out at 2200 GMT on the day of the accident.

The Department of the Environment report on the collision was published on 4

March 1976 and tests showed no equipment fault on the train. Post-mortem

evidence indicated that at the time of impact the driver's hand was on the

brake handle, rather than in front of his face to protect it. Witnesses were

interviewed; some passengers on the train reported that the train accelerated

when entering the station, and some witnesses standing in the station reported

that the driver, 56-year-old Leslie Newson, was sitting upright in his seat and

looking straight ahead as the train passed through the station. The state of

the motor control gear as found after the accident indicated that power had been

applied to the motors until within two seconds of the impact.

The

six day rescue operation involved 1324 firemen, 240 policemen, 80 ambulance

men, 16 doctors and numerous voluntary workers and helpers. The last body to be

brought out of the tunnel was that of the driver, Leslie Newson, a 56 year old

husband and father of two children.

Mystery

has surrounded the cause of the accident, and to this day no-one has been able

to explain why it happened. The Official Department of the Environment Report

on the accident reveals that the train was old, dating from 1938, but it and

the braking system were all in good working order.

Despite

all the investigations, the eye-witness evidence and the various theories, no

conclusive reason has ever been given for the cause of the crash, except

‘driver error’. Was Newson suicidal, was he taken ill or was he simply

distracted by something? Nobody will ever know what the driver of train 272 was

thinking as he drove into Moorgate Station at 8.46 that terrible morning.

A

SECOND plaque in memory of 43 people who died in the Moorgate Tube disaster in

1975 was unveiled in 2015, to commemorate the 40th Anniversary of

the disaster. The black granite memorial at Finsbury Square has the names of

all those killed. Its installation was organised by historian Richard Jones

with support from Islington Council.

|

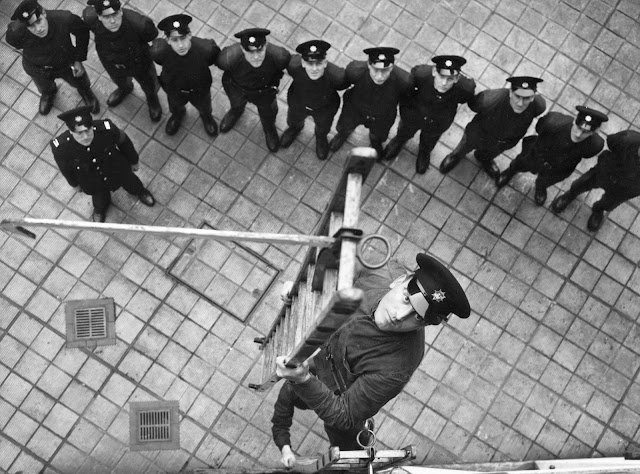

| Chief Officer Joe Milner talking to his crews. |

Among those at the ceremony was retired fireman Brian Goodfellow. He

had been stationed at Clerkenwell fire station and was part of the initial crews

that attended the Moorgate disaster. This is his story of the shocking events 43

years ago:

“I

was driving the emergency tender that day. We went downstairs with all our

gear, thinking it was a ‘train into buffers’ situation, but we soon got the

call saying it was a major action procedure – this meant there were multiple

casualties and at least 50 walking wounded. We went inside what we thought was

the first carriage, assuming the driver would be in there, but it was actually

the third – there were two more carriages up ahead.

What

really sticks in my mind was the human jigsaw puzzle of casualties... if you

imagine a fully-loaded, underground carriage at a 45 degree angle, in the shape

of a W – everyone had been catapulted into the end of the carriage. The rescue

situation was very arduous, a lot of images still stay with me. We were there

from nine to five that day, with only glasses of water for relief. The

Salvation Army brought some food but no one wanted to eat because of the

atmosphere. And when we went back to the fire station there was an icy cold

silence. I wanted to keep cleaning my teeth, someone else kept washing their

hair, and someone else was washing their hands. Back then we didn’t understand

what it meant, but we were trying to wash away the memories.

But

in every tragedy there are gems of human recovery and happiness and one thing I

remember is a man who was walking injured. He was being asked to leave the

station but he said: ‘No, my wife’s in there. I’m not leaving till I see her.’ Then

a woman came out from behind a pillar who was also just walking injured, and

when they were reunited, the only way I can describe it is love and happiness

going up that escalator... with all the tragedy going on behind them.

That’s

the image that I remember so well. It gave me a second wind to go back in there

and do what needed to be done.”

Steve

Gleeson is a retired London fire officer. As a fireman in 1975 he was part

of Lambeth's Emergency Tender (Blue Watch) crew that day. In the London Fire

Brigade’s 43rd anniversary account Steve gave his memories of

that tragic incident. He arrived at Moorgate Underground station around 1000

hours on the Friday morning of the incident.

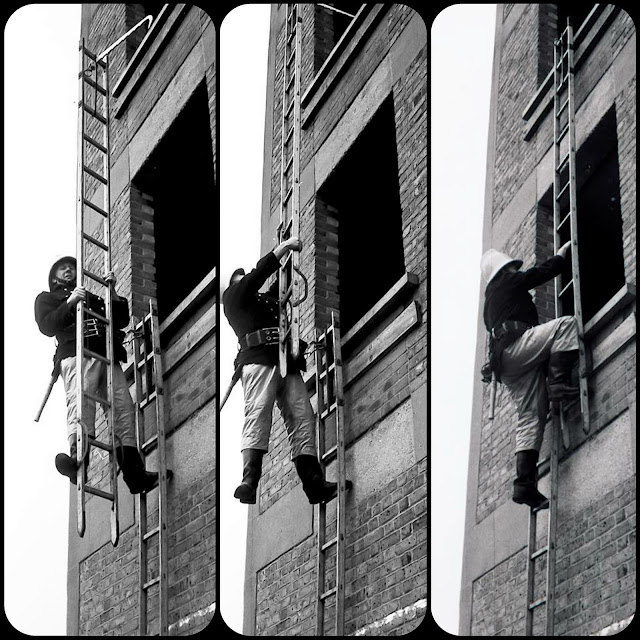

Steve

recalled: "We were immediately told to get our spreading and cutting gear and

take it down to the platform level. As we were taking our gear down, firemen

were guiding casualties, covered in dust and grime, up the other escalators to

safety, as well as to grab more equipment. We quickly began to get an idea of

the size of the incident but we didn't really know what to expect until we got

to the platform.

Once

there we found a carriage half at the platform and half into the tunnel but on

a slant up into the ceiling. Our brief was to go further into the tunnel and

start rescuing the trapped people. At the time, we didn't know how many people

there were or what condition they were in."

He

made his way through a 2ft gap between the tunnel wall and the side of the

train. As he advanced past the first carriage, Steve found crews had already

started working to release people trapped in the wreckage.

Steve

continued: "A crew from Clapham had already cut a hole in the end of the

train carriage and we used that to go through to the next carriage. In there we

met a senior officer who asked us to get into the roof of a carriage. We were

right at the very front of the train – about 10 to 12 feet behind the driver's

cab. While we were working on the roof of the cab, Paddington's crew were

working on freeing a woman below. Crews worked tirelessly in the dark, dusty

tunnel, which was illuminated by only old style battery ‘box’ lamps to rescue

the trapped people.

In

order to fit through some of the gaps in the carriages – and to avoid heat

exhaustion, as temperatures reached up to 33C Steve, and the other firemen,

removed their helmets, tunics, belts and axes. None of the crews working down

there wanted to leave. They all wanted to stay and help the casualties they

were with. We had to all be ordered out by senior officers to allow fresh crews

to come in and to give us a break from the ever increasing temperatures we were

working in."