London’s fire brigades have their roots embedded in the insurance

companies. The insurance fireman’s primary concern was the saving of

property, not life, in order to keep the insurance companies level of

claims down. The saving of life was a secondary affair. It was in

response to growing public disquiet over the loss of life for fire that

the Fire Escape Society was originally formed in London in 1828. The

wheeled escape ladders were strategically placed in streets to be ‘run’

by conductors to the fire with the object of effecting any necessary

rescues. The Society was funded by private donations but failed to

secure sufficient financial support and was eventually absorbed by the

newly-formed Royal Society for the Protection of Life from Fire in 1836.

London’s first municipal fire brigade was formed in 1833, called the London Fire Engine Establishment its Chief, termed Superintendent, James Braidwood reported to the insurance companies. Although Braidwood would see the introduction of the ‘new’ steam fire engine none of his stations housed an escape ladder. Braidwood died at a Tooley Street fire in 1861 and an Irishman, Capt. Eyre Massey Shaw took over the helm of the LFEE.

The Metropolitan Fire Brigade was established by an Act of Parliament in 1866. It was funded by the ratepayers of London. In 1867 it took over responsibility for the Royal Society’s escapes, by which time the number of escape stations had reached 85. The Royal Society would concentrated its efforts in the provinces but finally discontinued its rescue activities in 1881 as it was seen as a local authority responsibility i.e. the fire brigades role.

Operation from its Watling Street headquarters Shaw had over twice as many ‘escape’ stations as he had fire stations. His firemen, who had been on escape duty in the streets all night, often had to be sent straight out to a fire as soon as they returned to the station in the morning. It was not unusual for a fireman to be on duty for 120 hours without a break.

Many of the escape firemen performed heroic acts of bravery. Some died in the process. In 1871 Fireman Joseph FORD was on escape duty when called to a fire in Grays Inn Road. With the aid of a policemen the pair ran the ladder to the burning house. Five times Ford ascended the escape ladder and rescued five with hardly a pause for breath, sliding them down the copper chute situated on the underside of the ladder. Then he heard another in distress, a woman, at the top of the building. Almost exhausted he climbed the ladder and bringing the woman half way down and dropping her to safety. He himself became entangled in the chute for a while. As the crowd watched in horror Ford was being roasted alive by the blaze. Finally, and frantically, he freed himself only to fall the ground where he died. Such was the outpouring of public sympathy that generous donations raise some £1000.00 for Ford’s widow. Ford’s employer, the then Board of Works (the forerunner of the London County Council) promptly cancelled Ford’s widow pension stating the she and his children were now adequately supported!

Capt. Shaw moved to the new Metropolitan Fire Brigade (Southwark) headquarters in 1878. His Brigade strength stood at 48 fire stations and 107 fire escape station. There were over 450 escape ladders situated across London at both locations and many held in reserve. Firemen were still ‘running’ the 50 foot escape ladders to fires. By 1889 the station numbers had risen to 55 and 127 respectively. Although there were 127 escapes manned every night there were no funds available for any day-time escape service!

Shaw tendered his resignation with the now London County Council in the autumn of 1891. His successor, his deputy, was Capt. Simmons. His five year tenure did little to influence the availability of the escape ladders. His term of office end when the LCC effectively sacked him for misconduct and paid him off. It was his successor Capt. Wells RN. who is credited with introducing both the escape cart and the ‘long ladder’, a 75 foot version of the escape ladder. These extra-long escapes were also carried on a horse drawn vehicles and placed strategically across London. It was first the first time that the Brigade had a dedicated life-saving appliance. Escape-carts later became escape-vans, and were fitted with first-aid firefighting equipment. Horses slowly gave way to the introduction of the motorised escape-vans in 1906 and with increased mobility and speed the escape stations were eventually withdrawn right across London. (The first horse drawn turntable ladders were introduced in 1905.)

Over the next thirty years things improved both in equipment and a marginal improvement in firemen’s conditions but the 50 wheeled escape ladder remained the same. However, how it was carried changed in 1934 with the introduction of the first dual purpose appliances capable of being either a pump-escape or a pump. That policy would remain to the present day with the most commonly used front line fire engines. Self-propelled appliances had replaced all horse drawn engine, the last withdrawn from service in 1921. With the increased acquisition of turntable ladders the 75 foot wheeled escapes were scrapped too.

The escape ladder was the fireman’s preferred ladder of choice. It was strong and stable but did have some limitations when it came to pitching it restricted spaces. However, used in conjunction with a first floor ladder (placed at the top of the escape ladder, or providing a platform to use hook ladders to scale further up a building, or bridged to span a gap at lower levels it was an extremely versatile and robust firefighting ladder.

During WWII its use was restricted to London’s regular firemen who rode the pre-war pump escapes and despite the wholesale devastation caused by enemy bombing and the fires they caused day-to-day fires still occurred across London and the escape ladder remained the primary rescue ladder of the Brigade.

Sadly, in December 1951 three London firemen died and many more were seriously injured when a wall collapsed at the major fire at Eldon Street. The upper walls crashed down on a number of escape ladders being used by crews to direct jets into a burning warehouse. They were the first operational firemen deaths involving a wheeled escapes since Victorian times. Tragically other firemen also died engaging the pump-escape competitions, where crews raced against each other in slipping and pitching the escapes to a drill tower and performing a rescue by a ‘live’ carry-down. The pump-escape competitions were later suspended and then cancelled altogether by the 1960s.

| |

| The escape conductor, Mr Wood, at the Blackfriars escape post. SE London. |

London’s first municipal fire brigade was formed in 1833, called the London Fire Engine Establishment its Chief, termed Superintendent, James Braidwood reported to the insurance companies. Although Braidwood would see the introduction of the ‘new’ steam fire engine none of his stations housed an escape ladder. Braidwood died at a Tooley Street fire in 1861 and an Irishman, Capt. Eyre Massey Shaw took over the helm of the LFEE.

The Metropolitan Fire Brigade was established by an Act of Parliament in 1866. It was funded by the ratepayers of London. In 1867 it took over responsibility for the Royal Society’s escapes, by which time the number of escape stations had reached 85. The Royal Society would concentrated its efforts in the provinces but finally discontinued its rescue activities in 1881 as it was seen as a local authority responsibility i.e. the fire brigades role.

|

| An escape cart at the Cystal Palace fire station (No 88) in Penge. |

Operation from its Watling Street headquarters Shaw had over twice as many ‘escape’ stations as he had fire stations. His firemen, who had been on escape duty in the streets all night, often had to be sent straight out to a fire as soon as they returned to the station in the morning. It was not unusual for a fireman to be on duty for 120 hours without a break.

|

| The escape station at Brockwell Park. Herne Hill. |

Many of the escape firemen performed heroic acts of bravery. Some died in the process. In 1871 Fireman Joseph FORD was on escape duty when called to a fire in Grays Inn Road. With the aid of a policemen the pair ran the ladder to the burning house. Five times Ford ascended the escape ladder and rescued five with hardly a pause for breath, sliding them down the copper chute situated on the underside of the ladder. Then he heard another in distress, a woman, at the top of the building. Almost exhausted he climbed the ladder and bringing the woman half way down and dropping her to safety. He himself became entangled in the chute for a while. As the crowd watched in horror Ford was being roasted alive by the blaze. Finally, and frantically, he freed himself only to fall the ground where he died. Such was the outpouring of public sympathy that generous donations raise some £1000.00 for Ford’s widow. Ford’s employer, the then Board of Works (the forerunner of the London County Council) promptly cancelled Ford’s widow pension stating the she and his children were now adequately supported!

Capt. Shaw moved to the new Metropolitan Fire Brigade (Southwark) headquarters in 1878. His Brigade strength stood at 48 fire stations and 107 fire escape station. There were over 450 escape ladders situated across London at both locations and many held in reserve. Firemen were still ‘running’ the 50 foot escape ladders to fires. By 1889 the station numbers had risen to 55 and 127 respectively. Although there were 127 escapes manned every night there were no funds available for any day-time escape service!

Shaw tendered his resignation with the now London County Council in the autumn of 1891. His successor, his deputy, was Capt. Simmons. His five year tenure did little to influence the availability of the escape ladders. His term of office end when the LCC effectively sacked him for misconduct and paid him off. It was his successor Capt. Wells RN. who is credited with introducing both the escape cart and the ‘long ladder’, a 75 foot version of the escape ladder. These extra-long escapes were also carried on a horse drawn vehicles and placed strategically across London. It was first the first time that the Brigade had a dedicated life-saving appliance. Escape-carts later became escape-vans, and were fitted with first-aid firefighting equipment. Horses slowly gave way to the introduction of the motorised escape-vans in 1906 and with increased mobility and speed the escape stations were eventually withdrawn right across London. (The first horse drawn turntable ladders were introduced in 1905.)

| ||

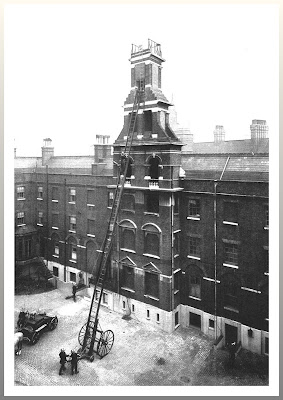

| The No 1 station and Metropolitan Fire Brigade HQ at Southwark. |

|

| The 'long' ladder at the Southwark headquarters. |

Over the next thirty years things improved both in equipment and a marginal improvement in firemen’s conditions but the 50 wheeled escape ladder remained the same. However, how it was carried changed in 1934 with the introduction of the first dual purpose appliances capable of being either a pump-escape or a pump. That policy would remain to the present day with the most commonly used front line fire engines. Self-propelled appliances had replaced all horse drawn engine, the last withdrawn from service in 1921. With the increased acquisition of turntable ladders the 75 foot wheeled escapes were scrapped too.

The escape ladder was the fireman’s preferred ladder of choice. It was strong and stable but did have some limitations when it came to pitching it restricted spaces. However, used in conjunction with a first floor ladder (placed at the top of the escape ladder, or providing a platform to use hook ladders to scale further up a building, or bridged to span a gap at lower levels it was an extremely versatile and robust firefighting ladder.

During WWII its use was restricted to London’s regular firemen who rode the pre-war pump escapes and despite the wholesale devastation caused by enemy bombing and the fires they caused day-to-day fires still occurred across London and the escape ladder remained the primary rescue ladder of the Brigade.

Sadly, in December 1951 three London firemen died and many more were seriously injured when a wall collapsed at the major fire at Eldon Street. The upper walls crashed down on a number of escape ladders being used by crews to direct jets into a burning warehouse. They were the first operational firemen deaths involving a wheeled escapes since Victorian times. Tragically other firemen also died engaging the pump-escape competitions, where crews raced against each other in slipping and pitching the escapes to a drill tower and performing a rescue by a ‘live’ carry-down. The pump-escape competitions were later suspended and then cancelled altogether by the 1960s.

The demise of the wheeled escape ladder came in the mid-1980s. Cost and problems of maintenance and difficulty in replacement were cited as the cause, but firemen of the time bemoaned the ladder’s passing. A ladder that had served firemen and firefighters well was consigned to the history books and to fire service museums.

|

| Fenchurch Street in 1983. The last London hook ladder rescue and the escape ladder next to the replacement Lacon ladder. |

The wheeled escape ladder. Circa 1830 to 1984. RIP.