In the

early hours of the morning on Thursday 23rd January 1958, firemen

arrived at the Smithfield Meat Market. By the time the blaze was finally contained,

days later, two members of the London Fire Brigade were dead and a further twenty-six

were hospitalised.

On

arrival, the fire was discovered to be deep within the basement labyrinth. The

crews from Clerkenwell fire station were among the first on site. Station

Officer Jack Fort-Wells (47) and Fireman Richard Daniel Stocking (31) would later

head down into the dense smoke that filled the extensive basement. Tragically,

they never returned to the surface alive.

After 25 hours,

and around 3am on the Friday morning flames engulfed the ground floor of the

Market. The intense heat and flammable gasses from the basement escaped and

fire quickly consumed the entire Poultry Market. As the flames reached over 100

feet, it was decided that the fire was too fierce to extinguish and the brigade

began focusing their efforts on protecting the surrounding buildings.

The ‘stop’

message was received at 16:45 on Friday 24th January. Over 700 oxygen cylinders

had been used, worn by some 400 firemen in breathing apparatus in the three

days of firefighting operations. A total attendance of more than 1700 officers

and firemen, with 389 pumps and other appliances attended from 56 of the LCC’s

58 fire stations as well as some from surrounding fire brigades. The final

brigade appliance withdrew from the scene on the 7th February.

Smithfield.

The original Poultry

Market was designed by Sir Horace Jones. The London Central (Smithfield)

Markets, of which the poultry market was part, consisted of four buildings of

almost equal size. They covered an area of around ten acres. Each one some 250

ft by 240 ft. Of particular note were the basements to these buildings which

were slightly larger due to them running under the adjacent pavements. The

building where the fire originated started was known as The Poultry Market.

At

the time of the fire it was estimated that around 800 tons of poultry, game and

meat was stored at the market. The single story buildings were constructed of

load bearing brick walls with ornamental towers around 70ft high at the corners

and centres of buildings. It had a pitched slate on boarding roof, wired

louvers topped the structure. The roof was supported on cast iron columns and

beams. None of these beams were protected against fire.

The

basement was constructed with a concrete floor. The ground floor which was

about 2ft. thick was formed from brick arches, and covered with 8 inch thick

stone slabs. Inside the building the galleries and ground floor were

partitioned to form offices and shops. The partitions were built from timber,

lath and plaster on timber studwork, breeze blocks rendered with plaster. The

basement had been divided into around 90 storage compartments. Many had been

divided further into sub-compartments. Whilst some compartments were accessible

via doors from basement corridors, others could only be accessed by entering

through trapdoors in the ground floor of the market. Access in the basement was

further reduced by a railway tunnel which ran diagonally through it. This

tunnel was bridged at 2 points using stepped crossovers, but these crossovers

had limited headroom.

Some

access to the basement was available by electric lifts within the building and

trapdoors which were set in the pavement outside. Further entry to the basement

could be made via tunnels that were used to pass refrigerated air use to cool

the basement. These tunnels contained heavy insulated doors that formed air

locks to help prevent the escape of cold air. One large section of the basement

was insulated with slab cork covered with cement, elsewhere the basement was

insulated with granulated cork, slab cork or slag wool held in place with

timber studwork or match boarding. A large amount of bituminous sheeting was

used in conjunction with the insulation.

One

fireman’s story.

Fireman John Bishop

started his career in the London Fire Brigade at the age of 20 in February 1949.

He had already served six years at sea in the Merchant service joining at just

14 years of age! This red haired young fireman started his days at Clerkenwell,

the Divisional headquarters of the former LCC B Division which cover the City

of London and the East End. It was one of four Divisional stations which

covered the London Fire Brigade’s 58 stations. It was here he learned his craft

alongside war-time firemen and those returned from active duty in WWII serving

with the armed forces.

John, or ‘Ginger’ as he

was known would learn his craft the hard way; especially when he ended up in

hospital for several days after attending a refuse lorry fire in a council

yard. By 1954 he was promoted to Leading Fireman rank and still at Clerkenwell.

Then on the 11th May 1954 Clerkenwell’s pump-escape and pump were

called to a fire at Langley Street, off Covent Garden. It was fate that saved John

from possible death and certain serious injury. The crews had been called to a five

storey warehouse, approximately 45 ft. x 100 ft. packed with crates and market

materials. The building had recently been fumigated with a paraffin-based

chemical. Whilst two firemen stayed outside to operate the pump seven others,

led by Station Officer Frederick Hawkins, went inside to deal with the small

fire. Leading Fireman Bishop was detailed to walk around the back of the

warehouse as the others entered and climbed the stairs. Suddenly the fumes

inside exploded. The resultant shock waves brought the roof down. The shingled

roof covering was still reinforced with cobble stones which had been placed on

top during the war as protection against incendiary bombs. The whole lot came

crashing down burying all those on the stairs. The dead and injured were

entombed in tons of debris. Whilst assistance was summoned John and his two

colleagues fought desperately to reach their fallen colleagues.

(Station Officer

Frederick Hawkins and fireman A E J Batt-Rawden died at the scene. Five other

firefighters were seriously injured. Sub Officer Sidney Peen, Leading Fireman

Ernest Datlin and firemen Kenneth Aylward, Frederick Parr, Richard Daniel

Stocking and Charles Gadd were all removed to hospital. Charles Gadd died from

injuries, three of the injured required plastic surgery treatment. John Bishop escaped

with bruises.)

By January 1958 John Bishop had been promoted to

Sub Officer rank. On the 23 January he was the acting Station Officer in charge

of the Red Watch at Whitefriars fire station and whose ground adjoined the Smithfield

Meat Market complex.

The first call to the Brigade

was received at 02.18 a.m. It was to a fire at ‘The Union Cold Storage’

premises in Smithfield Street. The Lambeth control room, located in the

basement of the Brigade Headquarters, mobilised Clerkenwell’s pump-escape, pump

and emergency tender, Whitefriars pump plus Cannon Street’s turntable ladder. It

was evident on arrival that there was fire within the basement, the problem was

finding it.

Bishop’s crew was the first to arrive at the

Smithfield Meat Market fire. He, together with another fireman, were preparing

to investigate the thick smoke coming up from the markets basement when Station

Officer Jack Fort-Wells from Clerkenwell arrived. As it was Fourt-Wells’s

ground, and he was the substantive Station Officer, he immediately took charge.

His first objective was to find the extent and seat of the fire. He was aided

in his task by having not only firemen using breathing apparatus carried on the

two pumps but the special breathing apparatus crew riding his station’s

emergency tender. Fourt-Wells

not only had difficulty in assessing the extent of the fire but how to gain

effective access to it. Eight minutes after his arrival, and with no swift

resolve in locating the fire, Fourt-Wells sent the first assistance message

making pumps four.

Station

Officer Fourt-Wells had been taken by an employee to the plant, room tunnel,

where he encountered thick smoke. Returning to the surface Fourt-Wells, rigged

in breathing apparatus and was joined by his emergency tender crew. The BA team

entered the tunnel to locate the source of the smoke. The plant, room tunnel

was searched but no fire was found. Information was received that the fire

could be in the main basement that was secured with a padlock. Eventually the

crew found the door and were provided with a key. By this time the crew were running low on oxygen.

(Of the 5 crew members, one gauge read 10 atmospheres one gauge read 5

atmospheres and the other gauge was on zero atmospheres.) Three of the firemen left

the basement hearing their Station Officer say “leave the door open I‘m just,

going to take a look”. Within minutes of the exiting men leaving the basement

the alarm was raised. However, but due to the complex nature of the basernent

it was almost an hour before the bodies of Station Officer Fourt-Wells and

Firefighter Stocking were located and brought out.

John Bishop was interviewed about the fire by Channel

4 Television some years ago. In it he related the early stages of the Smithfield

fire;

“When the first pumps arrived, thick acrid

smoke was pouring out of the market's maze of underground tunnels leading to

cold storage rooms.”

With the arrival of senior officers from the B Divisional headquarters

at Clerkenwell Fourt-Wells although in command, he and his crew members were in

the basement. John Bishop recalls the moment;

“Clerkenwell’s Station Officer and a fireman had

headed down into the dense smoke, never to be seen alive again”.

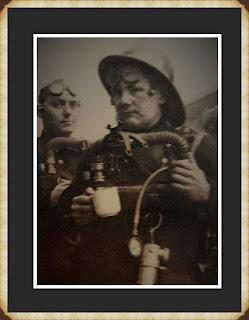

Station Officer Fort-Wells and ET fireman Dick

Stocking had entered the fire wearing their Mark IV proto oxygen breathing

apparatus sets, sets that they pre-war counterparts had worn in the 1920s. In

those early stages, with six BA carrying pumps and two emergency tenders in

attendance increasing numbers of firemen, wearing breathing apparatus, were

committed into the basement. John Bishop and his pump’s crew would be one of

scores of teams to enter the Smithfield basement. Again he relates his story;

“It was a maze and we used clapping signals. I

was going down the centre and I'd send men down a passageway here and there.

You would walk along one step at a time, with the back of your hand in front of

you in case you walked into something red-hot, making sure you were not going

to fall down a hole. All we could find was passageways with meat packed either

side from floor to ceiling. The smoke got thicker - you could eat it; black

oily smoke. It was very cold down there and you were cold, even though you were

sweating. That was fear.”

John Bishop would be

reunited with his former Clerkenwell workmate, Dick Stocking, for the very last

time, for it was he that led his Whitefriars crew in search of the two missing

men. There was intense activity as the frantic search got underway. But

possibly other lives may have been saved by the coolness of Assistant

Divisional Officer Lloyd (the first senior officer to arrive) who checked the

oxygen cylinder contents of each rescuer as they entered into the basement.

Even so many still put their own lives at risk by having less than half of

their full cylinder content. It was a crew from Manchester Square that located

Fourt-Wells under packages and carcasses of meat not far from their entry

point. His mouthpiece was on the floor and he was lifeless. They started to

return his body to the surface but were relieved of their gruelling,

unenviable, task by other firemen. Bishop found Stocking against a blank wall

in a dead-end passageway. He showed no signs of life. On his return to the exit

Bishop had to hand the task of recovery to other firemen as his own oxygen

supply had expired, but he made it back out.

For the next 24 hours crews

struggled to come to terms with the blaze. The cold January air turned to

excessive heat as crew after crew combated the dense smoke and worsening

conditions. Such were the arduous, physically punishing, conditions that BA

crews could not work for more than 10-15 minutes at a time.

Despite the determination of the firemen the

complexity of the

basement, the manner of its flammable insulation and stored meat products the intensity of the fire was able spread through much of two and a half acre maze of underground passages aided by air-ducts and ceiling voids. The dominance of the fire below ground forced superheated gases and smoke up into the street, heat which firemen had to struggle against even when bringing jets to bear though some of the pavement openings and external trapdoors.

basement, the manner of its flammable insulation and stored meat products the intensity of the fire was able spread through much of two and a half acre maze of underground passages aided by air-ducts and ceiling voids. The dominance of the fire below ground forced superheated gases and smoke up into the street, heat which firemen had to struggle against even when bringing jets to bear though some of the pavement openings and external trapdoors.

Smithfield was a blaze which had robbed the London

Fire Brigade of two of its own. It was a Clerkenwell fireman, who knew Fort-Wells

that described him as “One of the old

`smoke eaters’ who would not give up hunting for the seat of a fire…”

A

Smithfield worker.

George

Goodwin was an apprentice butcher working at Smithfield. He worked at a small

family butchers at 59 Long Lane. It was situated at the top end of the market

and as he arrived for work in the early hours of that Thursday morning already

there was a lot of police activity and plenty of fire engines at the Poultry

Hall. Smoke was rising from the vents in the walkway outside the market. Long

Lane was closed off and the meat carrying lorries were cleared from their

positions backed onto the entrances to the market to a place of safety.

As he watched the situation

changed and more and more fire engines arrived. The smoke got thicker and

blacker and hung over the market like a cloud. Not recalling exactly when but

rumours started to surface that there were a number of firemen hurt, possibly

some killed. The meat workers we were kept away from the activities taking

place but he wrote how he was “relieved I was not a fireman.” Crowds of market

men, in their long blue or white bloodied smocks, stood watching as the firemen

battled with the fire after the tragedy unfolded.

Timeframe of the Smithfield fire.

0218 Call to the

Union Cold Store-Smithfield Street.

B20 (Clerkenwell)

PE. P. ET

B36 (Whitefriars)

P

B35 (Cannon

Street) TL

0230. From Station Officer Fourt-Wells. Make pump

four.

B36 (Whitefriars) PE and B33 (Redcross Street) P plus

A4 (Euston) AFS Pump ordered. ADO Lloyd and DO Shawyer attending from B Div HQ

(Clerkenwell)

O246. From DO Shawyer. Considerable amount of smoke

issuing from basement store, market section. No fire yet. BA men searching.

0253. From DO Shawyer. Second ET required to

stand-by. D61

(Lambeth) ET ordered.

0255. From DO Shawyer. A building of 2 floors and

basement, about 300 ft x 300 ft, part of basement alight.

0307. Ex Tele call to Lambeth Control. Fire

Charterhouse Street. (DO Shawyer informed.)

0315. From DO Shawyer. Making an entrance at

Charterhouse Street.

0318. From DO Shawyer. Making entry from two

different sides of the fire. Smithfield Street and Charterhouse Street. The

fire has not yet been located. 4 additional pumps with BA required to stand-by. A4 (Euston) P from Clerkenwell. B32 (Bishopsgate) P

from Whitefriars. B27 (Shoreditch) P and D62 (Southwark) P.

0325. From DO Shawyer. Fire located on Charterhouse

Street side of incident.

0342. From ACO Cunningham at Smithfield Street make

pumps 8.

A1 (Manchester Square) P from Clerkenwell. D64 (Old

Kent Road) P from Whitefriars. B33 (Redcross Street) PE. B35 (Cannon Street)

PE. Brig HQ (Lambeth) CU. A1 (Manchester

Square) HLL.

0347. From ACO Cunningham. 3 emergency lights

required. Extent of fire still not known, access being made from all available

points.

Deputy Chief Leete mobile to incident.

0356. CU arrived and in control. (R/T 20)

0408. From ACO Cunningham. Make pumps 12.

B37 (Holloway) P from Redcross Street. A10

(Kensington) from Clerkenwell. B29 (Burdett Road) from Whitefriars. D66

(Brixton) P from Cannon Street.

(*On the make pumps 12; 4 PEs, 13 Ps plus 1 AFS

pump would be in attendance.)

0433. From Chief Officer. Order CaV at once with

refreshments for 100 men. (D61 Lambeth CaV ordered.)

0448. From Chief Officer. Second ambulance required

at Smithfield Market.

0459. From Chief Officer. 10 BA pumps required as

relief at 0600hrs.

(B21 Islington, B24 Homerton, B26 Bethnal Green,

B31 Shadwell, C42 Deptford, C43 East Greenwich, C50 Lewisham, D63 Dockhead, D60

Clapham, A3 Camden Town.)

0500. From Chief Officer. Make ambulances 4.

0507. From the Chief Officer. Fm Stropp removed to

hospital.

0514. From the Chief Officer Station Officer Fourt–Wells

and Fireman Stocking (B20) overcome by smoke and removed to hospital by

ambulance. (They were pronounced dead upon arrival.)

Friday 24th

1645. Stop message sent.

The Brigade of the late 1950s comprised of only

three principal officers; the Chief Officer and his two Assistant Chief

Officers (one nominated his deputy). All three remained in constant attendance

in excess of 24 hours before either the deputy (Mr Leete) or the ACO (Mr

Cunningham) was order to take charge of a major fire in Bermondsey.

Chief Officer Frederick Delve was no stranger to

major fires. However, the Smithfield fire would prove to be a ‘watershed’ for

the Brigade’s breathing apparatus procedures (procedures that had ramifications

for the UK fire service as a whole). For Delve and his men at Smithfield it would

be one of the most difficult breathing apparatus incidents faced in recent

peacetime history. Nor was Delve a stranger to men dying on his ‘watch. Nine firemen

and officers had died in the line of duty since the end of the World War II.

When the Chief Officer arrived at Smithfield he was

greeted by his crews facing thickening smoke and arduous conditions. Crews were

working underground, in breathing apparatus, in relays to seek out the fire and

attacked it wherever possible. Two emergency crews, also in breathing

apparatus, where situated at both entry points ready to be committed to seek

out colleagues in difficulty or find those overdue. Additionally a further

emergency crew stood by at the Brigade’s Control Unit ready to replace the other

emergency teams should they be required to enter the basement. The crews at

Smithfield were relived at about four hour intervals plus at the change of

watch at 0900 and 1800 hrs on the 23rd. Delve also discovered that

his officer’s attempts to get a feel of the layout of the basement were

seriously hampered due to the lack of employee knowledge about its layout and

locked doors.

Delve consolidated the work of Shawyer and

Cunningham. Yet despite all their attempts to direct the extinguishment of the

flames, and the tenacity of Delve’s firemen undertaking the task, a task which

had them working in the most challenging of conditions, the fire was gaining a

firm hold. It was spreading through the basement. Such were the conditions

during the morning of the 23rd that crews had to be withdrawn from the

Charterhouse Street entrance with all efforts concentrated on the West

Smithfield tunnel entrance. With day shift (Blue Watch crews) now fully engaged

attempts were made to create fire breaks in the flammable insulation by teams

of firemen. Large areas were painstakingly cut away from the basement walls and

ceiling. All to no avail, the fire continued on its path of destruction.

Flooding the basement was attempted and water was

applied from every possible vantage point. The Chief later reported that

500,000 gallons an hour was being pumped into the basement. (Individual pump

capacity in 1958 was in the range of 500-750 gpm.) However, the drains disposed

of the water before it could make any significant impact on the fire. Later the

flooding was abandoned as large quantities of water was penetrating nearby

underground railway tunnels.

Still with no noticeable effect from the previous

firefighting efforts by the late afternoon of the 23rd the Chief

chose to push the fire back from the Charterhouse Street side towards the lift

shaft in West Smithfield from where, it was hoped, the fire would vent itself.

The attack was made by fresh crews who inched their way into the basement. By

this point the heat was so great that crews had to be relieved every 10-15

minutes, even so many were overcome by the heat. They had to be assisted, or

carried, towards the entry point by colleagues, themselves affected by the

heat, and from where the semi-collapsed firemen were hauled up the lift shaft

by line before being removed to St Bart’s hospital by ambulance. Yet despite

the attrition rate of his firemen Delve pushed on with these tactics to advance

the attack on the fire. But as the heat and conditions below ground grew ever

more severe the attackers were forced back. Finally Delve withdrew his men

before they were overwhelmed entirely.

As night fell, and the Red Watch firemen returned

to the scene, it was hoped that the thickness of the ground floor, at almost 3

feet, would contain the fire. It proved not to be the case. Late on Thursday

evening the first breach in the ground floor became evident. Jets positioned to

contain the spread proved ineffectual. In the early hours of Friday morning

parts of the ground floor collapsed allowing for a massive escape of

superheated gases and flame to spread upwards. Crews working inside the Market

building were withdrawn. The intensity of the fire was such that the cast-iron

columns lost their structural integrity raising fears of the collapse of the

roof, which later transpired.

Delve, in anticipation of such developments had

previously ordered radial branches to the scene. It remains highly probable

that at this point in excess of 20 pumps were actively engaged in containing

the fire to the Poultry Market despite pumps not being increased beyond 12!

As the fire let forth its full ferocity it rabidly

consumed all before it. It was fuelled by the insulated match boarding wood,

wool, bituminous tar which had become deeply contaminated and impregnated with

animal fats through the years of lack of service and maintenance. The physics

of the now rapid fire spread was aided by the fact that the ground floor had a

smaller footprint than that of the basement below it. Therefore it acted as a

chimney allowing the furnace like temperatures to overwhelm the firemen’s

attempts to contain it. Delve was again forced to withdraw his crews and they

had to surround the blaze. There was no saving the Poultry Market. In the

darkness of that January morning the ornate corner distinctive towers collapsed

in spectacular fashion, the falling balls of flame adding to the pyre below.

At its height the 13 jets and 12 radial branches,

fed by 10 pumps and supplied by 18 street hydrants, were throwing 16,000

gallons of water per minute onto the blaze. It was left to the day watch to see

the blaze subdued, not least because it had consumed all the available fuel. It

was late afternoon that the STOP message was finally sent. Then the more

mundane activity of damping down and eliminating hot spots started. The Brigade

would remain at the scene in ever decreasing numbers until the 7th

February. It was during ‘damping down’ that

Fireman Handey (Bishopsgate) suffered serious injuries when he fell through the

floor into the basement.

The control room staff at the Lambeth headquarters had not only handled the challenging Smithfield fire in the period 23rd -25th January but also mobilised the Brigade to a further 259 separate incidents. In addition the Brigade dealt with 7 four pump fires, 1 six pump fire, plus an eight pump fire on the 24th in an office block in Southwark Street. This was followed by a fifteen pump at a Jam factory in Rouel Road, Bermondsey and a further twenty pump fire in the early hours of the 25th in a rubber dump/derelict warehouse, Poplar High Street, East London. Here both the West Ham and Essex fire brigades had to come to the aid of their London colleagues.

The control room staff at the Lambeth headquarters had not only handled the challenging Smithfield fire in the period 23rd -25th January but also mobilised the Brigade to a further 259 separate incidents. In addition the Brigade dealt with 7 four pump fires, 1 six pump fire, plus an eight pump fire on the 24th in an office block in Southwark Street. This was followed by a fifteen pump at a Jam factory in Rouel Road, Bermondsey and a further twenty pump fire in the early hours of the 25th in a rubber dump/derelict warehouse, Poplar High Street, East London. Here both the West Ham and Essex fire brigades had to come to the aid of their London colleagues.

The aftermath.

The City of London Inquest was open and adjourned

on the 24 January. The Coroner, Mr J, Milner-Holme. MA. approving the funerals

of Jack Fourt-Wells and Richard Stocking.

The funeral procession of the two Clerkenwell men

took place on the 30th January. Station Officer Jack Fourt-Wells and

Fireman Richard Stocking were each carried on a wreath laden turntable ladder.

Leaving Clerkenwell fire station with its honour guard the fire engines bearing

the men’s’ flagged draped coffins led the cortège through the Smithfield Meat

Market before moving on the South London Crematorium at Streatham

passing the Brigade Headquarters with it honour guard en-route. The men’s

funeral service was conducted by the Rev. D.F.Strudwick, himself a serving

London AFS fireman.

The full inquest of the two men

took place on the 28th February and lasted two and half days. Mrs

Fourt-Wells’s interests being represented by Andrew Phelen QC on behalf of the

Fire Officer Association. Mrs Stocking by Rose Heibron QC on behalf of the Fire

Brigade Union and Mr Davis QC representing the London County Council.Rose

Heilbron QC. was a legal pioneer in post war Britain. She practised mainly in

personal injury and criminal law and was the

second woman to be appointed a High Court judge. But in February 1958, at the

request of the Fire Brigade Union solicitors, she looked after the interests of

the Stocking family. Both Fourt-Wells and Stocking where found to have died

from asphyxia due to the inhalation of fire fumes (carbon monoxide poisoning)

when trapped in the unventilated maze of underground chambers below Smithfield.

Issues arose as to whether the men had proper supervision. Rose Heilbron placed

both Brigade’s officers, including Delve, and the world renowned pathologist,

Dr Keith Simpson, under detailed technical questioning. She left no stone

unturned.

|

| Rose Heilbron. QC. |

The jury

returned verdicts of ‘misadventure’ on the two deaths. The Coroner recommended

the adoption of an automatic warning device designed to be fitted to the

breathing apparatus set which would sound when the oxygen was running low. The

Coroner did not wish to look into the origin of fire and the cause of the blaze

was never ascertained. In his recommendations he also requested the

installations of a ‘dry’ sprinkler system installation in similar locations. Finally

he also required that a low cylinder warning device should be attached to BA

sets and further recommended that the LFB do so in a timescale of 2-3 weeks.

Breathing

apparatus procedures.

Following Smithfield reports

were submitted the Fire Brigade Committee of the London County Council by

Delve. Once again lessons were to be learned. Some of the problems which occurred

at Smithfield regarding BA procedures had occurred at two previous fires at

Covent Garden. Although a local (LFB) procedure was set up by 1956 following

the second fatal Covent Garden Fire. This involved the provision of a BA Control

Point. At Smithfield it was in Charterhouse Lane to record the entry of men

wearing BA into the incident. The Control Point consisted of no more than

blackboard and chalk. It recorded: Name, Station/location,

Time of entry and Time due out.

At Smithfield this

procedure proved invaluable. It indicated, later, in the incident that two men

were missing and overdue. However, following the tragic loss of life at

Smithfield there were concerted calls for a more comprehensive schedule of BA

procedures to be formulated. These calls came from Delve, Leete, his Deputy,

and Mr John Horner, General Secretary of the Fire Brigades Union.

Later that same year Fire Service Circular (FSC) 37/1958

was issued. It detailed the findings of the Committee of Inquiry and

recommended the following:- Tallies for BA sets; A Stage I and Stage II control

procedure for recording & supervising BA wearers: The duties of a control

operator: The procedure to be followed by crews: A main control procedure.

In the accompanying letter to the circular Brigades

were requested to report their observations and recommendations in light of

experience by the end of November 1959. There was at the time no specifications

for the design and use of guide or personnel lines. It was considered that more

experience had to be gained! Recommendations were, however, made in respect of

a specification for a low cylinder pressure warning device and a distress

signal device.

Finally, and in light of the views of Fire Brigades

following Smithfield and based on their own experiences, it was clear that the

use of BA would require more men to be better trained in its use and the safety

procedures. Subsequent guidance on the selection of BA wearers was provided in

FSC 32/1960 after agreement at the Central Fire Brigades Advisory Council on 27

July 1960. It recommended:-18 months operational service before BA training. A

possible age limit for wearers. Standards of fitness. Two BA wearers per

appliance equipped with BA.

Finally.

A

special word of thanks to Dave Goldsmith for sharing some of his extensive archive

material in the completion of this narrative. Other information has been taken

directly from to documents held at the Metropolitan Archives FB/GEN/2/124 Fire

at Poultry Market, Central Markets Smithfield E.C.1 - 23/1/58".

The

incident remains listed as a 12 pump fire! However the early attendance on the

23rd lists 18 pumping appliance (inc 1 AFS pump) plus specials. It

was possibly a cultural thing back then, requesting additional appliances

rather than making up? It was common pactice in the 1950s and 60s for senior/principal officers to request additional pumps to stand-by at the Control Unit then use them especially in protracted BA operations. 10-12 pumps fire with twice as many machines in attendance was not without precedent in the LFB.

It also appears

the Smithfield records are incomplete. Sight of the original fire report for Smithfield would

clarify some discrepancies. The LCC/LFB classifies the incident as a 20 pump

make-up, which given the statement of Delve to the Coroner and the LCC’s Fire

Brigade Committee supports this view. His own figures provides for an average

attendance of 20 pumps at 3-4 hourly intervals over the 23rd to the

24th. The 13 jets and 12 radial branches used required the

attendance of more than ‘12 pumps to deliver the amount of water required. Lastly,

it was stated, anecdotally, that at one point that smoke from the Smithfield

fire travelled through the catacombs into the basement of St Bart’s and the

hospital authorities even considered evacuation. However, this was not

mentioned in any LFB reports.

There

were errors made at Smithfield, but they have to be set in the context of excepted

practices of the time. As tragic as the deaths were the sacrifice was not in

vain. Lessons were learnt. They helped developed better BA procedures. It

remains both unfortunate and regrettable that it took their deaths to bring

about such change.